Last Wednesday, Jill Abramson, the first woman to hold the executive editor position at The New York Times, was fired.

In the rush to figure out how and why the respected journalist had been removed from one of The New York Times‘ highest positions, The New Yorker released one of the first reports on the change. The magazine’s article, entitled simply “Why Jill Abramson was Fired”, details a corporate “narrative” that Abramson had become too “pushy”.

The Times‘ usual far-left stance seems to falter in the high levels of corporate politics. Perhaps Arthur Sulzberger, Jr., publisher, and others at the newspaper’s very top fail to realize the motives this report reveals. Perhaps they’ve not yet figured out that, if Jill Abramson were a man, they’d be praising her assertive style rather than trying to excuse her termination. Framing female bosses as “pushy” and “bossy” is an example of gendered language in the workplace that reinforces the glass ceiling. Sulzberger and friends have only made their sexism more plain, whether they recognize it or not.

But maybe the Times‘ executives genuinely do not know that they discriminate based on gender. In response to an ongoing uproar (of which the New Yorker is part) over Abramson’s firing, Sulzberger released a statement claiming to justify the termination. In it, he attempts to dismiss claims of discrimination and utterly fails.

One of many assertions in the New Yorker article and others holds that Abramson approached management too brusquely over a possible wage disparity with her predecessor, Bill Keller. The New Yorker even quotes a “close associate” of Abramson’s confirming that “she confronted the top brass”. Largely focusing his proof of the Times‘ non-sexism, Sulzberger assured close followers of the story that “Jill’s pay package was comparable with Bill Keller’s.”

The New York Times‘ top executives appear to have entirely missed the point. The discrimination criticized is not simply a matter of pay difference, though it is by no means irrelevant. Gender inequality is more importantly an issue of perception. When, in the same report, Sulzberger points to Abramson’s “management of the newsroom” as the real cause of her firing, he reaffirms his new sexist image. The parts of Abramson’s style he points to amount to one basic complaint: Jill Abramson is a ‘pushy woman’.

The executive editor’s position is the highest-ranking in the Times‘ newsroom. Since 1964, nine people have held the position, all of them white men except Abramson and her successor, Dean Bacquet, who is an African-American man. As the first woman to hold the position in the paper’s history, Abramson represents a huge step towards breaking the glass ceiling in corporate environments. She wrote extensively on feminist issues while covering a wide range of other topics for the Times. In 2012, Jill Abramson was ranked #5 on the Forbes list of most powerful women. She’s wrote for Time, The American Lawyer, and The Wall Street Journal before joining The New York Times. She is a phenomenal and distinguished writer and will likely write more great things in the future.

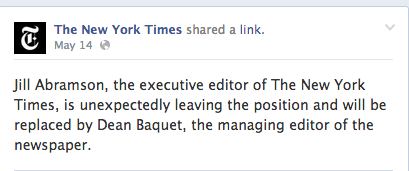

The New York Times’ removal of a great journalist from the executive editor’s position is a step backward for high-ranking gender minorities in the workplace. On the same day, the Times‘ Facebook page released the following short message:

In an attempt to avoid the outcry that immediately followed, the newspaper tried to shift the blame to Abramson herself, turning the focus instead to her successor. Media outlets from all over have criticized the paper’s sexism, but none have yet found this undeniable marker of failed deception and corporate sexism. Ironically, in the wake of the Abramson uproar, the newspaper has not yet gotten around to taking it down.

[Image Attribute: NY Times]